Underwater, there is no silence

Manuel Vieira, a researcher at MARE/ARNET at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon (Ciências ULisboa), analyses the soundscape of the ocean to understand how human noise interferes with fish communication.

The conference ‘Ambient Noise: the forgotten pollutant’, promoted by the Municipality of Estarreja, featured researcher Manuel Vieira, from the Fish Bioacoustics Lab, MARE/ARNET at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon (Ciências ULisboa), as its final speaker.

Invited to speak about the impact of noise on fish, he took the audience on a dive to where, as he says, ‘there is no silence’.

‘I tried to show that underwater there is a huge variety and quantity of sounds. But there is also a lot of anthropogenic noise that has an impact on various species, and we must be aware of that,’ he said.

Manuel Vieira was surprised by the audience's interest. Most of the conference panels addressed terrestrial noise pollution and its effects on human health. His presentation was the only one dedicated to the aquatic environment: ‘I think people liked this openness. It was a different perspective. And, as I was the only biologist, they asked questions about all animals,’ he laughs.

Fish can hear too

In the laboratory, the researcher studies how fish hear and produce sounds.

"Fish hear, some better than others. The fish considered to hear best is the goldfish, the one we have in aquariums (...) it has very special adaptations, with specialised bones connecting the swim bladder to the otoliths that allow it to hear pressure well. The charroco practically does not hear the pressure component of sound and should only detect the movement component of the particles (...) The sounds they produce are low frequency and fit well with what they need to communicate," explains the researcher.

Not all fish produce sound.

‘Goldfish are great at hearing, but not at producing sounds. It may be related to the importance of perceiving their own environment, but no one knows the real reason,’ he admits.

Fish that produce sounds do so in various ways: some vibrate their swim bladder with sonic muscles, ‘as if they were hitting a balloon’; others scrape bones against each other: ‘We have the case of the seahorse, whose skull has areas that scrape against each other and make clicking sounds,’ says Manuel.

The sounds actively produced by fish are used to communicate, defend their territory or during the breeding season.

‘The charroco sings to attract females. If it doesn't sing, the males won't have eggs in their nests,’ explains the researcher. ‘Sound may be essential for reproduction.’ Corvinas also form choirs at sunset, ‘a phenomenon that is not yet fully understood,’ he adds.

When human noise becomes deafening

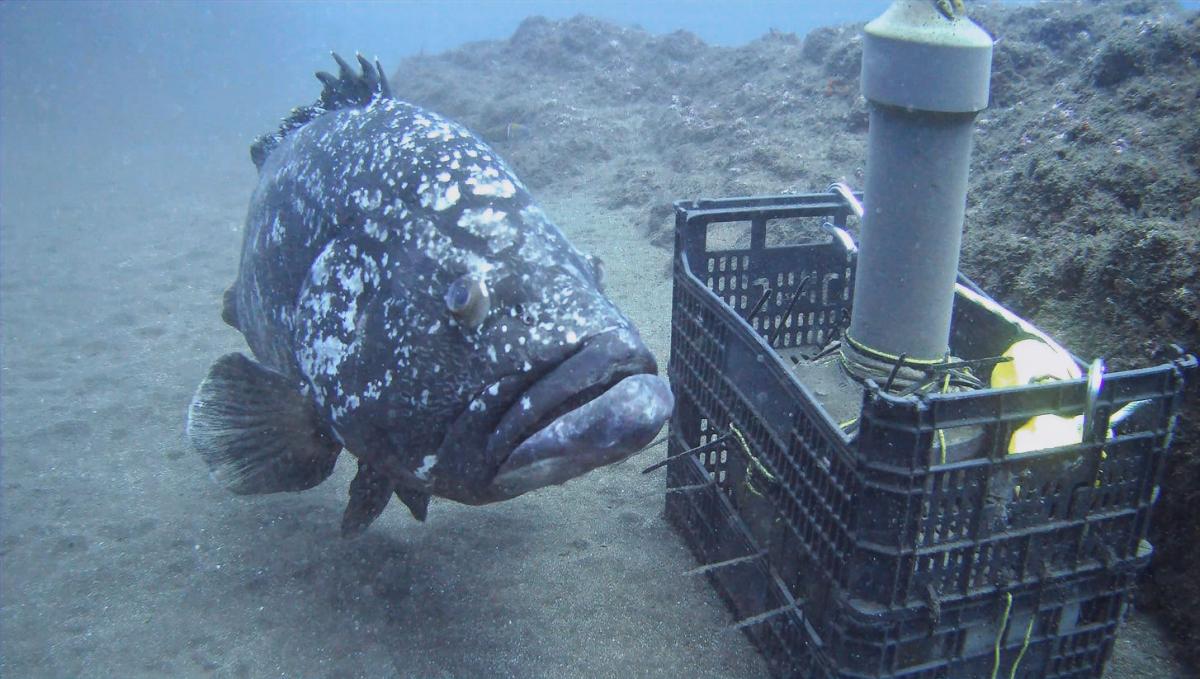

His work at the Fish Bioacoustics Lab focuses on passive acoustic monitoring and the use of artificial intelligence to analyse large volumes of recordings collected in places such as the Tagus estuary.

‘We place hydrophones underwater that record for months or years. Then, using automatic tools, we can detect daily, monthly or seasonal patterns and understand when certain sounds occur,’ says the researcher.

This data also allows us to assess the impact of anthropogenic noise: ‘We have seen, for example, that every time a boat passes by, the chorus of corvinas decreases or stops. The same happens with charrocos. We tested this under controlled conditions: we placed loudspeakers with boat sounds and they stopped singing.’

Noise interferes with communication and causes stress in animals.

“The fish can no longer hear their partners, neighbours or predators. In the case of charrocos, exposure to boat noise can make them less active, they sing much less, reproduce less and their eggs have a higher mortality rate,” describes Manuel Vieira. Even the larvae are affected. “We saw changes in the size and consumption of the yolk sac.”

How to protect the silence of the sea

When asked about possible solutions, Manuel Vieira advocates limiting maritime traffic in sensitive areas and creating sufficiently large zones to reduce noise propagation.

"It is not easy to limit traffic in some areas. Even in a protected area, if boats pass outside the area but nearby, the noise still reaches inside. We would need larger areas to protect biodiversity from surrounding noise pollution," he explains.

For Manuel, research is just one step on the road to raising awareness.

"My main message is simple: make sure people know that there is no silence underwater. Once they realise this, the implications become clear almost instantly. If sound is used by so many animals, then the noise we produce has consequences."

Manuel Vieira studied Biology at the University of Algarve and obtained his PhD in Science from ULisboa, where he conducts research on marine soundscapes and the acoustic behaviour of fish. His work at MARE/ARNET at ULisboa combines technology, biology and ecology to understand how the ocean sounds and what those sounds tell us about the life that exists in it.

For the researcher, listening to the sea is an important step in understanding what we are doing to it.

Find out more about Manuel's work here:

The swimbladder does not enhance hearing in the Lusitanian toadfish.

Reproductive success in the Lusitanian toadfish: influence of calling activity, male quality and experimental design.

Temperature mediates chorusing behaviour associated with spawning in the sciaenid Argyrosomus regius.

Boat noise interferes with Lusitanian toadfish acoustic communication.

Boat noise impacts Lusitanian toadfish breeding males and reproductive outcome.

Boat noise impacts early life stages in the Lusitanian toadfish: A field experiment.

Textby Vera Sequeira e Manuel Vieira

Photographs by Camara Municipal de Estarreja e MARE-ULisboa